Protestant Defense of the Old Testament Canon

That the Protestant Old Testament canon is that which was received by the Jews, and Jesus Himself

The information in this article is drawn heavily, with much godly appreciation, from the scholarly work of Roger Beckwith in his book The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism

In polemics with Roman Catholic Apologists, it is often alleged as an attack against Protestants that Martin Luther disagreed with certain books of the Bible, and so he just tossed them out. And that is why the Catholic Bible contains more books than the Protestant Bible.

Now people in “the know” understand that this is historical fiction. While it is true that Martin Luther would openly express doubts about the canonicity of certain books (like James) this is not what lies in the background of his rejection of the Apocrypha. For you see, he was far from the first Christian to hold to this position. As a matter of fact, Jerome who translated what became the Latin Vulgate (the official Bible of the western church in Luther’s day) himself rejected these books as canonical! In actuality, the western church, or Roman Catholic church as it became known after the time of the Reformation, did not have an official definition of the canon until the Council of Trent in April of 1546!

The debate has continued to rage on ever since, but in our day the issue of canon is usually brought up by Rome’s apologists. Roman Catholics think they have an easy argument, “you can’t know the canon without an infallible teaching authority”. And since Rome claims to have such an authority, Roman Catholics feel at ease saying “the Church tells me these books are canon, and I trust the church.” Unfortunately, it is Protestants who usually feel the most unsettled about this question. But what I hope to bring before you in this present study, is that a very solid case can be made for the Protestant position on the canon, both on Biblical and historical grounds. It is true that the question of canon is not as easily answered from the Protestant side, sense we can’t just flip to an official declaration of canon somewhere,1 and so I am going to do my best to condense the key issues and make them understandable so that you can put these things in your back pocket and carry them with you, that you are equipped to give a defense when it is asked of you.

The two key points that are going to be addressed are 1.) The Jews, by the time of Christ, had a recognized and settled canon, and then 2.) The identification of what these canonical books were. The two questions are, obviously, related but they are distinct. Both points are going to be addressed utilizing evidence from three main sources: Jewish literature leading up to and around the period of the first century, the witness of the early church, and the New Testament itself. For some strange reason, the New Testament is usually discredited as a reliable historical source in scholarship, when in fact it is quite literally the most reliable historical source for this period of history! Not to mention God wrote it! As a matter of fact, as a Christian it is quite striking to me that some of the most telling evidence we have in answering the two points mentioned above come from the lips of Jesus Christ Himself, the greatest Jewish teacher.

A fully-orbed theology of canon is not the issue of this particular study (although it is my intention to write up a fuller explanation of the Reformed view of canon in the future). Suffice it to say, for know, that this author believes that since God Himself is the ultimate source and standard of human knowledge, that He does not need any authority outside of Himself to reveal to His covenant people what the canon of Scripture is. With that being said, the Apostle Paul (himself a highly educated former Pharisee) under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit tells us in Romans 3:2 that “the Jews were entrusted with the oracles of God”. τὰ λόγια τοῦ θεοῦ is the phrase Paul uses in speaking of the “oracles”, or “sayings” (λόγια) of God which Beckwith has shown was a common way of referring to the inspired Scriptures.2 Therefore, the inspired Apostle believes that the Jews have accurately received the Scriptures, not that he would sign off on each and every interpretation they made, but that they did have the Scriptures Paul affirms.3 Therefore, we can say that a Christian who accepts the New Testament must also accept as canonicals those oracles, or books which the Jews (at least in Paul’s day) had accepted as Scripture. With this theological point established, we can move on into the defense proper.

That the Jews Had a Settled Canon

Titles for the Canonical Writings

Closely related to what was just seen in Romans 3, we can recognize that the Jews had a settled canon because, well, they had the ability to refer to a body of canonical writings. As we saw, one of the ways these books could be referenced was with the title “the oracles” or “the oracles of God”. Roger Beckwith gives us a list of these various titles found in contemporaneous Jewish literature:

“The collection is called (i) ‘the Law and the Prophets and the Others that have followed in their steps’, (ii) ‘the Law and the Prophets and the Other Ancestral Books’, (iii) ‘the Law and the Prophecies and the Rest of the Books’, (iv) ‘the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms’, (v)‘the Laws, and the Oracles given by inspiration through the Prophets, and the Psalms’, (vi) ‘the Law and the Prophets’, (vii) ‘Moses and the Prophets’, (viii) ‘the Laws and the accompanying Records’, (ix) ‘the Law’, (x) ‘the (Most) Holy Scriptures’, (xi) ‘the Scriptures laid up in the Temple’, (xii) ‘the Scriptures’, (xiii) ‘Scripture’, (xiv) ‘the (Most) Holy Books’, (xv) ‘the Book of God’, (xvi) ‘the (Most) Holy Records’, (xvii) ‘the Records’, (xviii) ‘the Record’, (xix) ‘the Most Holy Oracles’, (xx) ‘the Divine Oracles’, (xxi) ‘the Inspired Oracles’, (xxii) ‘the Written Oracles’, (xxiii) ‘the Oracles of the teaching of God’, (xxiv) ‘the Oracles of God’, (xxv) ‘the Oracles’, (xxvi) ‘the Holy Word’, (xxvii) ‘the Divine Word’, (xxviii) ‘the Prophetic Word’.”

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (London: SPCK, 1985), 105.

That it was possible for someone to simply use a title to refer to this collection of books indicates that not only was there a collection to be referred to, but that the collection was commonly understood. You see, a general title like the ones mentioned above can only be meaningfully used if you assume that the person you are speaking to is going to understand what that title is in reference to. In the same way, when you are at church today and someone references “the Bible” or “the Scriptures”, those titles are used fruitfully because the group understands the collection of books you are referring to.

You’ll notice in the Gospels that when Jesus is dialoguing with the Jews (even in cases of theological disagreement) that He is able to reference “the Scriptures” (Matthew 21:42, 22:29, 26:56, Mark 12:10, 24, 14:49, Luke 4:21, 22:37, John 5:39, 7:38, 10:35, 13:18, 17:12) or “the Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 5:17, 7:12, 11:13, 22:40, Luke 16:16, Luke 24:44) or even “the word of God” (John 10:35). The New Testament gives zero indication that there was any confusion over the body of literature Jesus was referring to.

The Role of the Temple

You may have noticed that one of the titles Beckwith mentioned was “the Scriptures laid up in the Temple”. What we see is that the Temple played a key role in not only the fact that there was a canon, but also in the identification of those particular books. What is even more significant about this, is that because the Temple was destroyed in AD 70, seeing its role in the question of canon will show us that the canon was understood prior to the Temple’s destruction in AD 70. One of the things this shows us is that the Hebrew canon was not created as a response to Christianity, but that it was already established as Christianity began to flourish.

The idea of laying certain holy books in a temple, or some other sacred place, is something well attested in the ancient world, and we see it practiced amongst the Jews.4 The premise that lies behind such a practice is that “the laying-up of something in the Temple had the effect of dedicating it to God”,5 and since only what is “holy”, or acceptable to God, could be dedicated to Him, those books which were laid up in the Temple would’ve been those recognized as holy prior to their dedication. The Jewish-Roman historian Josephus testifies to this reality of “Scripture laid up in the Temple” (Antiquities 3.1.7, 4.8.44, 5.1.17). We know from the Mishnah that the High Priest would spend the night prior to Yom Kippur in the Temple, staying up reading from the books that were present in the Temple (Yoma 1).

That certain books were dedicated to God (laid up in the Temple) demonstrates a recognition on the part of the Jews (prior to AD 70) that there were certain books which were sanctified as holy. Related to this is the notion that these books rendered the hands ceremonially “unclean” (Kelim 15.6). This notion is clarified elsewhere, in that these holy books made the hands unclean should they be removed from the Temple (Tos. Kelim B.M. 5.8). Evidence suggests that gave these writings their ceremonial qualities were not simply the fact that they were present in the Temple, but their actual contents as well. “Holy Scriptures: According to their preciousness is their uncleanness. But the books of Homer, which are not precious, do not impart uncleanness to hands” (Yadayim 4:6).

What must be recognized is that not only did the Jews have a conception of especially holy books, precious in comparison to non-holy books (like the writings of Homer) but that because of the sanctity of these books, they were laid up in the Temple. The Harvard Scholar Moses Stuart commented on the “wisdom of Providence” in depositing the Scriptures in the Temple where they were protected and guarded from any corruption.6

The Cessation of Prophecy, or the Closing of the Canon

That there was a canon has been demonstrated in the previous two sections, but what we are now going to see is that there was also a recognition amongst the Jews that the canon was closed, that prophecy had ceased. But first, let’s define what we mean by a closed canon. When we speak about the canon being closed, we mean that there was a general and widespread recognition of the contents of the canon, and an understanding that no books were going to be added and taken away. Notice the key words “general” and “widespread”. We do not mean that there was 100% unilateral agreement, and not a single dissenting opinion or controversy. If this was the standard for a closed canon, than we would have to confess that such a thing never has existed in the history of religion. Not all sects of “Christendom” today agree on the canon, but none of these sects (at least the conservative parties) deny that there is a canon.

What we see happening in the history of Israel, with the death of the prophet Malachi, is an understanding that the Holy Spirit had ceased His prophetic work amongst the people. Interestingly, this was one of the Rabbinical arguments against the canonicity of the book of Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), “The books of Ben Sira and all the books which were written from then on do not make the hands unclean” (Tos. Yadaim 2.13). The explanation for this is that “With the death of Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi the latter prophets, the Holy Spirit ceased out of Israel” (Tos. Sotah 13.2). This statement not only tells us about the Rabbinical understanding that the canon had been closed, but it also tells us that these men believed the Holy Spirit was active in the inspiration of the Scriptures. Even the book of 1 Maccabees states that “prophets ceased to appear among them” (1 Maccabees 9:27).

This leads us into the identification of what the canonical books were, since the Spirit’s work in this capacity ceased with the death of Malachi (Malachi being the last written book in the Protestant canon), we can conclude (with the Rabbis of old) that any books written after Malachi’s death are not canonical. Ecclesiasticus itself contains statements referring to the already established canon (the law and the prophets) in its prologue.

This is even more striking when the internal evidence of Malachi is considered, which looks forward to the coming of the Lord Himself as the book ends with anticipation.

“Behold, I send my messenger, and he will prepare the way before me. And the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple; and the messenger of the covenant in whom you delight, behold, he is coming, says the Lord of hosts. 2 But who can endure the day of his coming, and who can stand when he appears? For he is like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap.” Malachi 3:1–2 (ESV)

5 “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and awesome day of the Lord comes. 6 And he will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, lest I come and strike the land with a decree of utter destruction.” Malachi 4:5–6 (ESV)

The Identification of the Canonical Books

It has already been established from the testimony of the Rabbis, Josephus and Jesus Christ Himself that there was an established Hebrew canon in the first century. The question of identification is the next question, which books were canonical?

The Twenty-Two

Josephus, who mentions that the Scriptures were laid up in the Temple, elsewhere speaks of the Scriptures as numbering 22 books, and he even says that this is what “every Jew” has believed for “long ages”. Here is his critical statement:

“For we have not an innumerable multitude of books among us, disagreeing from and contradicting one another [as the Greeks have], but only twenty-two books, which contain the records of all the past times; which are justly believed to be divine; and of them five belong to Moses, which contain his laws and the traditions of the origin of mankind till his death. This interval of time was little short of three thousand years; but as to the time from the death of Moses till the reign of Artaxerxes, king of Persia, who reigned after Xerxes, the prophets, who were after Moses, wrote down what was done in their times in thirteen books. The remaining four books contain hymns to God, and precepts for the conduct of human life.”

Against Apion 1.8 Flavius Josephus and William Whiston, The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1987), 776.

Josephus mentions “twenty-two books… which are justly believed to be divine”. Five of Moses, thirteen books of the prophets, and four books containing “hymns to God, and precepts for the conduct of human life”. Josephus does not give us a direct list of these books, as we see in Christian writers, but we do see some recognition of what the books are in the numbering.

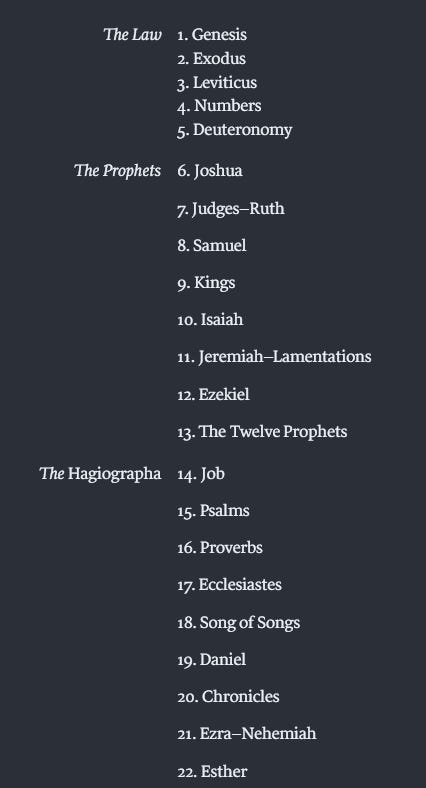

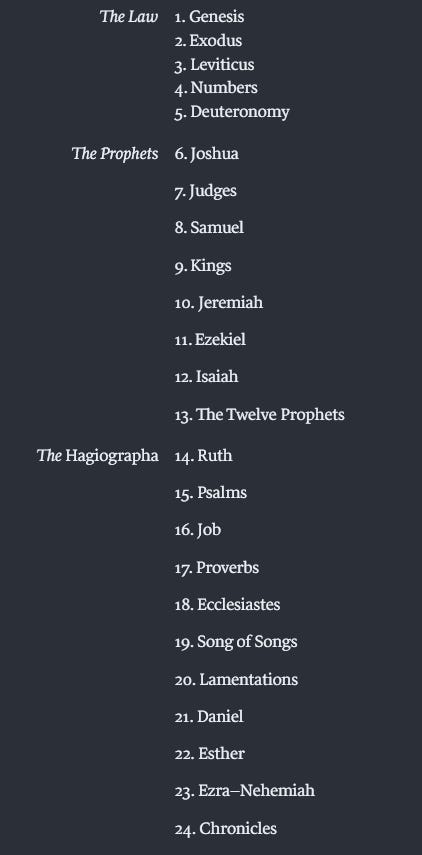

At this point, we should talk about the number 22. For you see, the twenty-two number was a “title” just as much as it was an actual number. Beckwith notes the fact that there was a desire to link the number 22 with the fact that there were 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet.7 Now the way this was accomplished was by combining certain books together, for example, tying Ruth with either Judges or the Psalms, this is why you also have Jews speaking of 24 books during this time period. 24 reflected the number, whereas 22 was both a number and a title, and they referred to the same books. You may think it strange, but nevertheless, this was what happened. Please note that the very fact Josephus (or anyone else) can give a number of the books testifies to the fact that there was an established understanding of the Hebrew canon. As a matter of fact, Josephus writes not only of the divine origin of these books, but that their consistency far surpassed what the Greek writings contained. Beckwith (examining both Jewish and Christian testimony) identifies the books in the following way:

“Like Philo (De Abrahamo 1), [Josephus] knows the books of Moses as five, and these are, of course, the five books of the Hebrew, Samaritan and Greek Pentateuch, as the use made of them in his Antiquities shows. His thirteen books of the Prophets are, in all probability, Job, Joshua, Judges (possibly with Ruth), Samuel, Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah (possibly with Lamentations), Ezekiel, the Twelve Prophets, Daniel, Chronicles, Ezra–Nehemiah, Esther. Likewise, his four books containing hymns and precepts are Psalms (possibly with Ruth), Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs (or, if one of the last two is omitted, the other together with Lamentations).”

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (London: SPCK, 1985), 253.

How this would have worked with the 22 or 24 numbering can be seen in the following layouts:

Naming the Books

The earliest lists we have, like in the figures above, of the canonical books come from Christian sources. Christians (believing what Paul said in Romans 3:2) in the early period actually went to Jewish communities and teachers, learning from them what the canonical writings were. And so when looking at Christian sources, we must be careful students of history. It will not do to simply look at a consensus of the fathers. The testimony of any father, or Christian author, has more weight to it the more this particular father knows about Hebrew language, history and custom. Hence, when Jerome and Augustine disagree over the Hebrew canon in the early part of the 5th century, Jerome (who at one point lived in Bethlehem and studied Hebrew under Jewish Rabbis) has a weightier testimony than Augustine (who is primarily working in Latin).

Patristic writers, with a knowledge of either Hebrew or Jewish customs, who provide us with a list of the Hebrew canon are Melito of Sardis, Origen, Cyril of Jerusalem and Jerome.8 Origen and Jerome explicitly acknowledge that their lists came from the Jews, so we will look at them here.

Origen:

“It should be stated that the canonical books, as the Hebrews have handed them down, are twenty-two; corresponding with the number of their letters.” Farther on he says: The twenty-two books of the Hebrews are the following: That which is called by us Genesis, but by the Hebrews, from the beginning of the book, Bresith, which means, ‘In the beginning’; Exodus, Welesmoth,9 that is, ‘These are the names’; Leviticus, Wikra, ‘And he called’; Numbers, Ammesphekodeim; Deuteronomy, Eleaddebareim, ‘These are the words’; Jesus, the son of Nave, Josoue ben Noun; Judges and Ruth, among them in one book, Saphateim; the First and Second of Kings, among them one, Samouel, that is, ‘The called of God’; the Third and Fourth of Kings in one, Wammelch David, that is, ‘The kingdom of David’; of the Chronicles, the First and Second in one, Dabreïamein, that is, ‘Records of days’; Esdras, First and Second in one, Ezra, that is, ‘An assistant’; the book of Psalms, Spharthelleim; the Proverbs of Solomon, Meloth; Ecclesiastes, Koelth; the Song of Songs (not, as some suppose, Songs of Songs), Sir Hassirim; Isaiah, Jessia; Jeremiah, with Lamentations and the epistle in one, Jeremia; Daniel, Daniel; Ezekiel, Jezekiel; Job, Job; Esther, Esther. And besides these there are the Maccabees, which are entitled Sarbeth Sabanaiel.”

Cited in Eusebius of Caesaria, “The Church History of Eusebius,” in Eusebius: Church History, Life of Constantine the Great, and Oration in Praise of Constantine, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. Arthur Cushman McGiffert, vol. 1, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1890), 272.

Beckwith notes the absence of the 12 Minor Prophets as a mistake.9 His statement “besides these there are the Maccabees” suggests an acknowledgement on his part that these books, though important, were outside of the canon.

Jerome:

“That the Hebrews have twenty-two letters is testified by the Syrian and Chaldæan languages which are nearly related to the Hebrew, for they have twenty-two elementary sounds which are pronounced the same way, but are differently written…

The first of these books is called Bresith, to which we give the name Genesis. The second, Elle Smoth, which bears the name Exodus; the third, Vaiecra, that is Leviticus; the fourth, Vaiedabber, which we call Numbers; the fifth, Elle Addabarim, which is entitled Deuteronomy. These are the five books of Moses, which they properly call Thorath, that is law.

The second class is composed of the Prophets, and they begin with Jesus the son of Nave, who among them is called Joshua the son of Nun. Next in the series is Sophtim, that is the book of Judges; and in the same book they include Ruth, because the events narrated occurred in the days of the Judges. Then comes Samuel, which we call First and Second Kings. The fourth is Malachim, that is, Kings, which is contained in the third and fourth volumes of Kings. And it is far better to say Malachim, that is Kings, than Malachoth, that is Kingdoms. For the author does not describe the Kingdoms of many nations, but that of one people, the people of Israel, which is comprised in the twelve tribes. The fifth is Isaiah, the sixth, Jeremiah, the seventh, Ezekiel, the eighth is the book of the Twelve Prophets, which is called among the Jews Thare Asra.

To the third class belong the Hagiographa, of which the first book begins with Job, the second with David, whose writings they divide into five parts and comprise in one volume of Psalms; the third is Solomon, in three books, Proverbs, which they call Parables, that is Masaloth, Ecclesiastes, that is Coeleth, the Song of Songs, which they denote by the title Sir Assirim; the sixth is Daniel; the seventh, Dabre Aiamim, that is, Words of Days, which we may more expressively call a chronicle of the whole of the sacred history, the book that amongst us is called First and Second Chronicles; the eighth, Ezra, which itself is likewise divided amongst Greeks and Latins into3 two books; the ninth is Esther.

And so there are also twenty-two books of the Old Testament; that is, five of Moses, eight of the prophets, nine of the Hagiographa, though some include Ruth and Kinoth (Lamentations) amongst the Hagiographa, and think that these books ought to be reckoned separately; we should thus have twenty-four books of the old law. And these the Apocalypse of John represents by the twenty-four elders, who adore the Lamb, and with downcast looks offer their crowns, while in their presence stand the four living creatures with eyes before and behind, that is, looking to the past and the future, and with unwearied voice crying, Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty, who wast, and art, and art to come.

This preface to the Scriptures may serve as a “helmeted” introduction to all the books which we turn from Hebrew into Latin, so that we may be assured that what is not found in our list must be placed amongst the Apocryphal writings.”

Jerome, “Prefaces to the Books of the Vulgate Version of the Old Testament,” in St. Jerome: Letters and Select Works, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. W. H. Fremantle, G. Lewis, and W. G. Martley, vol. 6, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1893), 489–490.

After the citation from Jerome cuts off, he goes on to list which books are “Apocrypha”.10

What we see in both of these lists is a recognition of the 22 number we saw with Josephus, only with the books explicitly identified. Since these men learned this information from Jews, there is little reason to doubt that their 22 was the same 22 as Jews like Josephus. And, we see consistency with the Protestant canon of the Old Testament. From this historical data, we see that ancient Jews, early church fathers, and protestants have a basic agreement as to the Hebrew canon.

Now, let’s get to the really fun stuff!

The Witness of Jesus Christ to the Hebrew Canon

As mentioned earlier on in this article, our Lord Jesus Himself attests to the title of “the Law and the Prophets” when speaking of the Hebrew Scriptures. But in Luke 24:44, he actually identifies (what we have seen in other sources already) the threefold division of the Hebrew canon:

“Then he said to them, “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.”” Luke 24:44 (ESV)

Of course, Jesus’ main point here is not a discussion of the canon, but rather that the contents of that canon were written about Him. This key theological point not being discarded, our present study is specifically concerning the canon, and we do see here Jesus agreeing with writers like Josephus and Jerome that there was a threefold division of the canon.

But as far as the actual contents of the canon, one of the most impactful statements we have in all of 1st century Jewish-Christian literature is what is said by our Lord Jesus in Matthew 23:35 and Luke 11:51

“34 Therefore I send you prophets and wise men and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your synagogues and persecute from town to town, 35 so that on you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth, from the blood of righteous Abel to the blood of Zechariah the son of Barachiah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar. 36 Truly, I say to you, all these things will come upon this generation.” Matthew 23:34–36 (ESV)

“49 Therefore also the Wisdom of God said, ‘I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and persecute,’ 50 so that the blood of all the prophets, shed from the foundation of the world, may be charged against this generation, 51 from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary. Yes, I tell you, it will be required of this generation.” Luke 11:49–51 (ESV)

Students of the Bible know that what Jesus is doing here is condemning the Jewish leaders of His day, and prophesying the destruction that would come upon that generation (culminating in AD 70). Jesus says that just as He was persecuted, so too did the Jews persecute the prophets. But notice something- He says “all the prophets” from Abel to Zechariah.

When Jesus does this, He essentially is making a connection between the beginning and the end of the Hebrew canon (recall that the Jews ended the canon with Chronicles, not Malachi). When Abel is slain his “blood is crying to [God] from the ground” (Genesis 4:10), when Zechariah11 is slain, he dies crying out, “May the Lord see and avenge!” (2 Chronicles 24:22). With Abel’s martyrdom taking place towards the beginning of the (Hebrew) Bible, Zechariah’s towards the end, Jesus is essentially saying that “all the martyred prophets from one end of the Bible to the other will be avenged on his own generation.”12

For Jesus’ words here to have the impact He intends, it presupposed an established order of the Jewish canon. But think about this, it also means that Jesus agrees with that canon.

You see, all the evidence from the Talmud, to Josephus, to the early church fathers is fascinating, and very important. But what really hits the nail on the head is when the sinless Son of God incarnate affirms what this historical data is teaching.

In Conclusion

Though the Protestant defense of the Old Testament canon is not as simple as Rome’s defense, the Protestant defense holds far more sway both historically and Biblically. I have tried my hardest to condense the historical information in a format that will be accessible to the average Christian. I don’t think it is necessary for you to have memorized every citation I provided (I haven’t), but at the very least you can remember, when your Roman Catholic (or Eastern Orthodox) friend challenges you on the canon some of the basics. For example, there was an established Hebrew canon in Jesus’ day, certain books (which rendered the hands unclean) were laid up in the Temple, the Jews (usually) numbered them as 22, and this 22 book canon agrees with church fathers like Jerome, is evidenced by Jesus Himself, and is the same canon Protestants have in their Bibles.

Please remember that this article was mostly an historical defense and study, not necessarily a theological one. For any of this to have any meaning, we must presuppose that the sovereign and Almighty God who wants His people to have His word, is able to bring that about.

In saying this, I am not even slightly suggesting that the epistemological authority claims of Rome are warranted. It is just that, from a certain standpoint, their claims of authority do give Roman Catholics a sense of certainty, but that doesn’t mean this certainty is actually valid.

The same phrase being found in Philo, as one example. Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (London: SPCK, 1985), 106.

The canon of Scripture is, of course, a separate issue than the exegesis of the Scripture.

ibid. 81

ibid.82

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (London: SPCK, 1985), 250.

Timothy Easley has provided us with a wonderful spreadsheet documenting canon lists here: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1nGCsgiJx7-TYlrczJ4FZBN2s4whmiwqLtZXbDcnEbeg/edit?gid=637845873#gid=637845873

“The omission of the Minor Prophets, whether due to Origen himself or to Eusebius, through whom we receive the list, must be accidental, since their canonicity was never disputed, and Origen both appeals to their authority in his extant writings and wrote a commentary on them, now lost.”

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (London: SPCK, 1985), 186.

“This preface to the Scriptures may serve as a “helmeted” introduction to all the books which we turn from Hebrew into Latin, so that we may be assured that what is not found in our list must be placed amongst the Apocryphal writings. Wisdom, therefore, which generally bears the name of Solomon, and the book of Jesus, the Son of Sirach, and Judith, and Tobias, and the Shepherd are not in the canon. The first book of Maccabees I have found to be Hebrew, the second is Greek, as can be proved from the very style.”

Jerome, “Prefaces to the Books of the Vulgate Version of the Old Testament,” in St. Jerome: Letters and Select Works, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. W. H. Fremantle, G. Lewis, and W. G. Martley, vol. 6, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1893), 490.

The one difficulty here is the identification of Zechariah. Jesus uses the patronym “son of Barachiah”, but the man we read about being slain between the altar and the sanctuary is said to be the son of Jehoiada. Beckwith explains that this was a common Jewish practice of “homiletic identification”. Basically, when two important men shared a name, their names would become conflated, essentially. Though this seems incorrect according to the modern English speaker, Jesus (a first century Jew) would have seen no problem with this. See Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (London: SPCK, 1985), 217–220.

ibid. 220