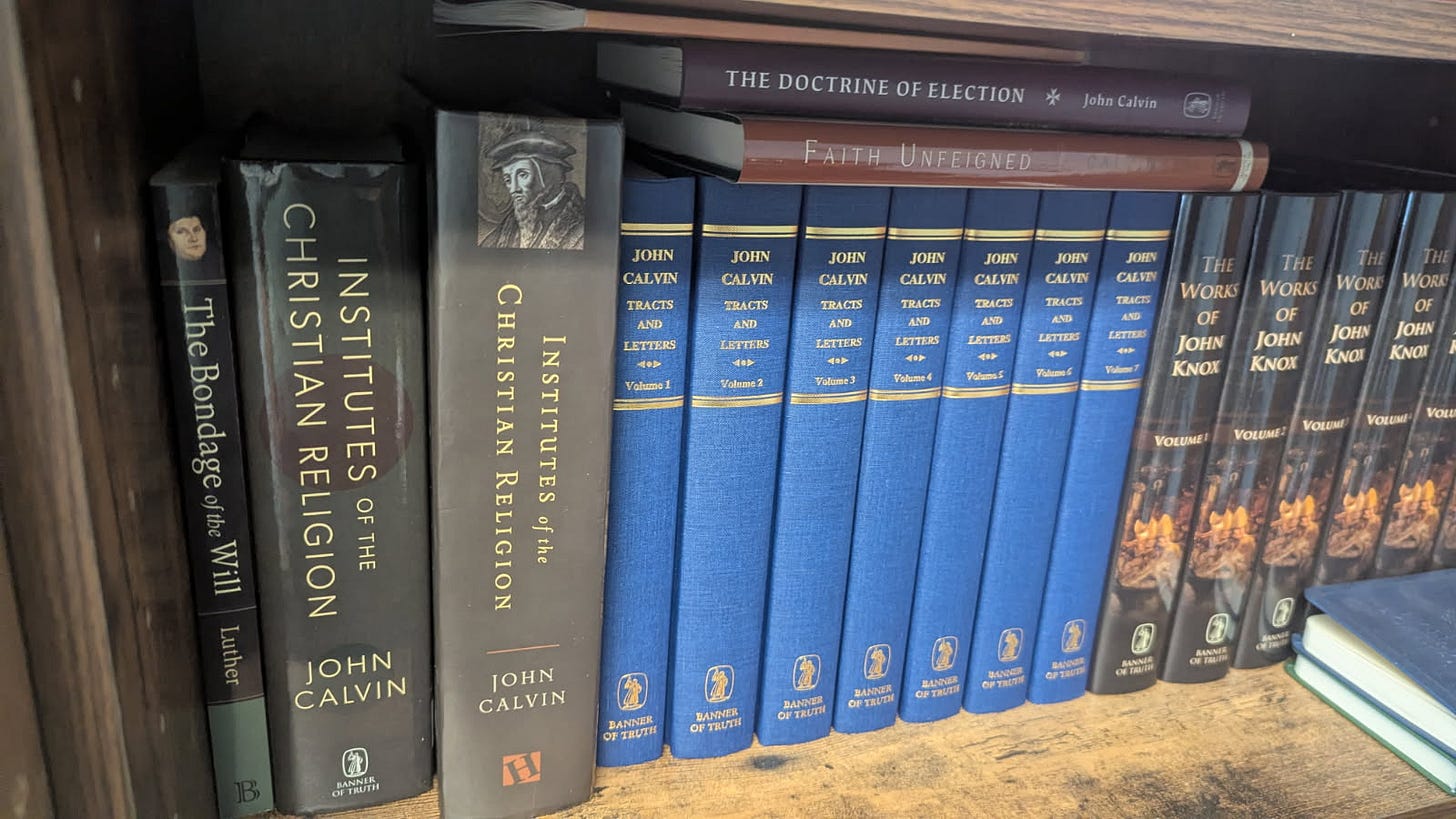

Why The Institutes of the Christian Religion Matters to Me

A Pivotal Work of Reformation Literature

*** I feel no shame in acknowledging that this essay began as an entry to Reformation Heritage Books’ giveaway. However, it took me about 3 minutes to go beyond their 300 word limit, so you get this to read. ***

Early on in my studies of Christian theology I had discovered lots of debate, often intense and emotional, concerning the topic of “Calvinism.” I knew that this had something to do with the idea of God predestinating things, but that was about all I knew. I wanted to learn more about it, and so I decided that there was no better way to figure out what “Calvinism” was than by reading John Calvin himself! I had a digital copy of the Institutes of the Christian Religion on my laptop and off I was to begin a theological journey that would lead to me to heavenly heights of devotion I had never anticipated in taking up and reading an almost 500 year old tome.

Now, I knew I needed to be on the lookout for words like “predestination” and “election”, but before we ever got to those topics Calvin needed to instruct me in knowledge itself. In the opening sentence of Book 1, he told me, “Our wisdom, in so far as it ought to be deemed true and solid Wisdom, consists almost entirely of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.” (1.1.1 Beveridge translation)

He went on to explain that the knowledge of God and knowledge of ourselves (and all earthly matters) were inseparable. In order to have a proper understanding of who you are, or of the world at large, you must see it as God sees it. Growing up in America and having gone to public school, I had imbibed this idea that there existed “common sense” that everyone basically agreed upon, but this notion of “neutral” or “unbiased” knowledge came crashing down as I realized that since all of creation belongs to God, I need to look to Him in order to understand it. Having God seated as the king of all knowledge revolutionized not only my theology, but the entirety of my thinking. Although when people hear the name “John Calvin” they begin to think about predestination, I honestly associate Calvin’s name with these issues of epistemology and knowledge of God more than anything.

Then Calvin exposited Romans 1, and demonstrated from the text of Scripture that every person knows God. To the pluralistic and democratic culture I was raised in, these seemed almost offensive. How can I say that everyone knows my God? That they are personally suppressing this knowledge? As scandalous as this all may seem, to disagree would be akin to disagreeing with God Himself.

I remember, rather vividly, reading chapters 16 and 17 on Divine Providence sitting in the back of a car as my family headed down south on a trip to North Carolina. It was one of the most intimate devotional experiences of my entire life. The comfort I received from recognizing God was in complete control of literally everything is a comfort I continue to turn to time and time again, when faced with doubt or discouragement.

“This being admitted, it is certain that not a drop of rain falls without the express command of God. David, indeed, (Ps. 146:9), extols the general providence of God in supplying food to the young ravens that cry to him but when God himself threatens living creatures with famine, does he not plainly declare that they are all nourished by him, at one time with scanty, at another with more ample measure? It is childish, as I have already said, to confine this to particular acts, when Christ says, without reservation, that not a sparrow falls to the ground without the will of his Father (Mt. 10:29). Surely, if the flight of birds is regulated by the counsel of God, we must acknowledge with the prophet, that while he “dwelleth on high,” he “humbleth himself to behold the things that are in heaven and in the earth,” (Ps. 113:5, 6).” (1.16.5)

Book 1 of the Institutes remains, for me anyways, my favorite extra-biblical theological literature I have ever encountered. It is still some of the most important reading I have ever done. In my physical copy of Beveridge’s translation, I wrote this at the end of book 1:

“Brother John Calvin in book first writes in such a way as to take the eyes off the page and on to God. I thank the Lord for this worthy Divine, who has helped me fall in love with His Providence.”

Book 2 covers the key issues of sin, the will of man, the Law and the person of Christ. If Book 1 focuses on the Creator, Book 2 focuses on the Redeemer.

The chapters on free-will are especially helpful. Utilizing passages of Scripture like Philippians 2, Calvin shows that because of man’s fall into sin, his will is in need of a powerful work of God’s grace if he is ever to be redeemed:

“Accordingly, he elsewhere says, not merely that God assists the weak or corrects the depraved will, but that he worketh in us to will (Phil. 2:13). From this it is easily inferred, as I have said, that everything good in the will is entirely the result of grace.” (2.3.6)

When Calvin later treats of our proper use of the Law, it flows from this idea that we can obey because God has redeemed the will.

Nothing is held in higher esteem or importance than Christ the Mediator, as Calvin describes His condescension and humility in taking on our flesh, only to result in His glorification. Chapter 15 describes the three-fold office of Christ as prophet, priest and king. The contrast between suffering and glory is stark, but we recognize that the Christian story is not one of perpetual suffering, but ultimately one of triumph:

“Not being earthly or carnal, and so subject to corruption, but spiritual, it raises us even to eternal life, so that we can patiently live at present under toil, hunger, cold, contempt, disgrace, and other annoyances; contented with this, that our King will never abandon us, but will supply our necessities until our warfare is ended, and we are called to triumph: such being the nature of his kingdom, that he communicates to us whatever he received of his Father.” (2.15.4)

Book 3 sets forth the doctrines of redemption, or, how the work of Christ spoken of in book 2 is applied to the believer.

Primarily, Calvin wants us to see that redemption is worked in us by the Spirit of God. Especially in the Spirit’s bringing about the gift of faith.

“I TRUST I have now sufficiently shown how man’s only resource for escaping from the curse of the law, and recovering salvation, lies in faith; and also what the nature of faith is, what the benefits which it confers, and the fruits which it produces. The whole may be thus summed up: Christ given to us by the kindness of God is apprehended and possessed by faith, by means of which we obtain in particular a twofold benefit; first, being reconciled by the righteousness of Christ, God becomes, instead of a judge, an indulgent Father; and, secondly, being sanctified by his Spirit, we aspire to integrity and purity of life.” (3.11.1)

Book 3 also contains Calvin’s chapters on predestination and election, which he is most well known for. These chapters are not to be disregarded, they are solidly exegetical. But we would do well to remember that the chapter immediately before the one on eternal election is the longest single chapter in the entire Institutes, and it is the chapter on prayer.

“To prayer, then, are we indebted for penetrating to those riches which are treasured up for us with our heavenly Father. For there is a kind of intercourse between God and men, by which, having entered the upper sanctuary, they appear before Him and appeal to his promises, that when necessity requires they may learn by experiences that what they believed merely on the authority of his word was not in vain. Accordingly, we see that nothing is set before us as an object of expectation from the Lord which we are not enjoined to ask of Him in prayer, so true it is that prayer digs up those treasures which the Gospel of our Lord discovers to the eye of faith. The necessity and utility of this exercise of prayer no words can sufficiently express. Assuredly it is not without cause our heavenly Father declares that our only safety is in calling upon his name, since by it we invoke the presence of his providence to watch over our interests, of his power to sustain us when weak and almost fainting, of his goodness to receive us into favour, though miserably loaded with sin; in fine, call upon him to manifest himself to us in all his perfections. Hence, admirable peace and tranquillity are given to our consciences; for the straits by which we were pressed being laid before the Lord, we rest fully satisfied with the assurance that none of our evils are unknown to him, and that he is both able and willing to make the best provision for us.” (3.20.2)

When he finally does consider the matters of election and predestination, he first gives us this warning:

“But before I enter on the subject, I have some remarks to address to two classes of men. The subject of predestination, which in itself is attended with considerable difficulty, is rendered very perplexed and hence perilous by human curiosity, which cannot be restrained from wandering into forbidden paths and climbing to the clouds determined if it can that none of the secret things of God shall remain unexplored. When we see many, some of them in other respects not bad men, every where rushing into this audacity and wickedness, it is necessary to remind them of the course of duty in this matter. First, then, when they inquire into predestination, let them remember that they are penetrating into the recesses of the divine wisdom, where he who rushes forward securely and confidently, instead of satisfying his curiosity will enter in inextricable labyrinth. For it is not right that man should with impunity pry into things which the Lord has been pleased to conceal within himself, and scan that sublime eternal wisdom which it is his pleasure that we should not apprehend but adore, that therein also his perfections may appear. Those secrets of his will, which he has seen it meet to manifest, are revealed in his word—revealed in so far as he knew to be conducive to our interest and welfare.” (3.21.1)

Calvin recognizes the delicate nature of his subject, that it is to be treated with utmost humility. But that does not stop him from confidently asserting the plain, Biblical truth that God saves whom He wills, and passes over others. As he walks through the discussion of the patriarchs in Romans 9, it is quite difficult to see it any other way.

Book 4 contains Calvin’s chapters on issues of ecclesiology, sacraments, and civil government.

He topples down the Pope with great polemical skill, arguing with the Bible as his authority and Church history as a witness. His arguments against the papacy are just as effective and valid today as they were 500 years ago (if not more so, as papal claims, and contradictions, have only expanded in the last few centuries).

In a similar fashion, the sacramental system of Rome is treated as the nonbiblical tradition of men that it is. I will not, at this time, expound my differences with Calvin on the subject of Baptism.1 Suffice it to say, for now, that his contribution to the topic remains key to the development of paedobaptist reformed thought on the subject. His chapter on the Lord’s Supper, on the other hand, fills my heart with delight.

In Sum

To conclude my appreciation post for the Institutes of the Christian Religion this Reformation month, let me honestly encourage you to read it. I can promise you, it isn’t boring. Calvin has a style and flare to his writing that is fresh, and personable. You get to the end of the book feeling like you know the man, not just his theology. His commentaries are the same way.

Probably none of us should expect, or even have the desire, to agree with every jot and tittle of what he says. So wherever you find yourself in the theological landscape, if you have not read this work, I highly encourage you to.

But the primary reason the Institutes of the Christian Religion matters to me is not merely one of historical curiosity, it is because the doctrines taught in the book are generally Biblical. As a matter of fact, Calvin himself routinely points you to the Scriptures as the ultimate authority, not the words of any father or council, and certainly not his own.

Although that would be an interesting thing to do in the future!