Up or Down? The Reformation and Natural Law/Theology

Thoughts on the development of western thought and a distinctly Christian philosophy

“For with you is the fountain of life; and in your light do we see light,” - Psalm 36:9

Let me ask you a question, it is a very simple one. How do you know what you know?

The common answer to this question is, “well I don’t know, and I get along just fine without thinking about it, so I’m not gonna worry about it”. Such is the pragmatic (and often intellectually lazy) spirit of 21st century Americans. It doesn’t matter how I know what I know, because I know that I do know!

The problem with this is that the answer to this question has central and fundamental implications for how we answer other, more (seemingly) important questions. Is there a God? Do human beings have rights? How should we live our lives? All of these questions have to do with this other question of how do we know what we know?

The question of knowing is called epistemology (theory of knowledge) and it should not surprise anyone to know that there have been radically different answers given to this question down through the ages, ever since the serpent challenged our first parents with “did God really say?”

Some of you may be aware of the current debates concerning issues of “natural theology vs presuppositionalism”, or “natural law vs theonomy”. Although I have strong opinions on these issues, and I do believe ultimately that presuppositionalism in apologetics and theology; and theonomy in ethics are the superior positions, it is not my goal right now to prove the validity of either position at this point in time. What I want to do here is give a historical examination and answer to the question of the (supposed) novelty of the presuppositional way of thinking. Reformed Thomists will often point to a tradition of Reformed Scholastics who had imbibed positions of natural theology and law as a way to “shut up” the Van Tillians. Stephen Wolfe’s book The Case for Christian Nationalism has made no small splash in current theological discourse, and in that book he explicitly states that he is not arguing for his position on theological grounds, but rather he appeals to what he considers to be the reformed tradition. From my perspective, although I found his book very interesting (and I even agree with Wolfe on certain particulars and points of application), I think that this method of argumentation fails to live up to the name the case for Christian Nationalism. The fact that people in history agreed with what you are saying is not an argument in favor of your position. It can serve to bolster and support your arguments, but this in and of itself is not an argument. Wolfe (and his followers) typically argue against theonomy by mocking it as a novel viewpoint, but they have not set themselves up to engage the issues.

Before we look at the history, let me say something very important, or rather let me quote something important from Dr. Joe Boot and that is that “the antiquity of an idea does not make it true.”1 If we are Reformed Protestants, then we ought to accept the Bible alone as our ultimate authority in understanding (that old question of how do we know what we know?). If our position is Biblical, it does not matter who stands against it. With that being said, let us begin to look at history, and we shall start at the very beginning.

The Garden

“Now the serpent was more crafty than any other beast of the field that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, “Did God actually say, ‘You shall not eat of any tree in the garden’?” And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden, but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the midst of the garden, neither shall you touch it, lest you die.’ ” But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not surely die. For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate, and she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked. And they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves loincloths.” - Genesis 3:1-7 (ESV)

Any true history of philosophy will begin here, not with Thales. What takes place here, at the very beginning of human existence, is the origin of the divide between theonomy2 and autonomy. What I mean here is a division in how we think. Will we think in accordance with God’s word and God’s ways (theonomy), or will we think on our terms and in our own ways (autonomy)?.

You might be puzzled that I point this divide out instead of a divide between God and Satan, more particularly. This is because, though in the grand scheme of the Biblical story and history of redemption, we see God conquering the devil and an antithesis between the children of God and the children of the serpent; I am specifically talking about the issue of how we think or how we know. You see, when Eve is faced there with two options in front of her: obedience to God’s word or the devil’s word; any amount of time that she spends pondering over the question, trying to decide how she will act, is time spent in sinful defiance to God. The God-honoring response would be to simply ignore the serpent and listen to God, but what Eve does is she makes a decision. She puts herself in the position of choosing between the two options. The fact that she would think for herself what it is she would do is the beginning of autonomous human reasoning then. The decision to make a choice is itself a choice, and an ungodly one at that. What I submit to you, then, is that the rest of human history (including up to our own time) is a war between thinking autonomously, or thinking in accord with God’s word.

Mankind fell in Adam. And the Scriptures teach that the fall of man into sin affects his mind as well. “In the pride of his face the wicked does not seek him; all his thoughts are, ‘There is no God’” (Psalm 10:4). Furthermore, the Bible describes the unbeliever as a “fool” (Psalm 14:1) not because the Scriptural authors are engaging in childish name calling, but rather because of the reality of the fact that the non-believers thinking is ethically opposed to God.

This is a key detail, so please do not forget it. The Bible isn’t teaching that unbelievers can’t do math or something like that. It is that the mind of the unbeliever is hostile to God (Romans 8:7). And so Paul declares,

“For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse. For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things.” - Romans 1:18–23 (ESV)

This passage tells us of God’s revelation to all mankind in nature, but it tells us that sinful man suppresses this truth. Please note that according to verse 18, it is the wrath of God which is being revealed from heaven. Those who use this passage to support their natural theologies tend to gloss over this point. I cite this passage here because it stresses the fact that the effects of sin, even upon the mind, are ethical in nature. At every single point, the unbeliever’s thoughts are “there is no God”.

God, being gracious, revealed Himself to Abraham and his descendants in a more special way, and ultimately in the Person of Jesus Christ. God’s revealed wisdom has always stood over and above human wisdom, because “the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom, and the knowledge of the Holy One is insight.” (Proverbs 9:10). In God’s light, that is in God’s revelation, do we understand the world around us. This is why the Apostle Paul was able to triumph over and against the Greek philosophers of his day (see Acts 17, 1 Corinthians 1) because with the word of God “we destroy arguments and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God, and take every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5).

The Biblical testimony we have just briefly glanced at may seem enough, in and of itself, to establish the fact that Christians must abandon any trace of autonomous human reasoning and seek a thoroughly Biblical Christian way of thinking, but sadly the church has not always recognized this.

Thomas Aquinas

We could have begun this study by looking at the early apologists, such as Justin Martyr, Tertullian, and Irenaus. There were Christians down through the centuries who were bright lights in demonstrating something of a Biblical view of knowledge, such as Augustine (354–430) or Anselm (1033/4–1109) who said, “I believe that I might understand”, but for the purpose of our present discussion we will look the angelic doctor of the Roman Catholic church, Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274).

The impact Aquinas had on western thought and western theology cannot be understated. Though I will be taking a critical approach to his way of thinking, it would be false to deny that (for better or worse) the world as we know it today is what it is because of Thomas Aquinas.

Thomas was no doubt a brilliant man, and from my reading, all accounts testify that he was a uniquely pious and spiritual man. That being said, he was also a man of his day. His ascetic life is evidence of this. He was a western medieval Christian thinker. Born in 1224, he essentially represents the culmination of medieval scholasticism. Men like Abelard and Lombard came before him, and so, of course, they would influence him. Aquinas, therefore, had a major defect in his theology, particularly his view of man (anthropology) and that is that he did not see the intellect or the mind of man as fallen3, but he believed it could operate just fine in the realm of nature (more on that later). Because of this, Aquinas felt free to draw from a number of non-Christian sources, including the Jewish Rabbi Maimonides, who infused his Jewish faith with Aristotelian philosophy.4 Similarly, what Aquinas will be most well known for is his own synthesis of western theology with Aristotelianism.

Aristotle had been in vogue with the Muslims for centuries, and as westerners (like Maimonides, mentioned above) interacted with Muslims, it was seen as necessary to bring Aristotle back into our knowledge. Thomas Aquinas was the man tasked with doing this very thing for the western church.

However, if you know anything about Aristotle, then you know that there is going to be an issue, and that is that Aristotle’s metaphysic is fundamentally opposed to and at odds with Christian theology. For example, Aristotle’s unmoved mover is a being so simple that he (or it) is essentially devolved into nothing more than “thought-thinking-thought”. The unmoved mover cannot think about, or relate to, this temporal world in any sense, for then it he would no longer be the pure simple being Aristotle (wrongly) concluded nature led him to believe. A being such as this cannot be reconciled with the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, for example, which posits that God exists in three distinct Persons who relate to one another. Aristotle’s unmoved mover cannot create ex nihilo (out of nothing), which is flatly contradicted by the creation account in Genesis 1.

Aquinas’ solution to this is to establish a division between faith and reason. Now it is not as though no one had ever distinguished between these two concepts before, or that no one ever thought there was a difference between the spiritual and material, things eternal versus things temporal or anything like that. What I am talking about is Thomas’ specific formulation of the two disciplines of faith and reason.

Aquinas allows man’s reason to run free. Man’s reason is sufficient for many things in philosophy and is even sufficient to discover truths about God. But for Aquinas, there reaches a point wherein man’s reason is limited. For him, this is chiefly in issues in regard to salvation, “It was necessary for the salvation of man that certain truths which exceed human reason should be made known to him by divine revelation.”5 And so even though he believes that man’s autonomous reason can discover certain truths about God, ultimately divine revelation is necessary for the fulness of understanding, and divine revelation will always trump natural reason:

“Even as regards those truths about God which human reason could have discovered, it was necessary that man should be taught by a divine revelation; because the truth about God such as reason could discover, would only be known by a few, and that after a long time, and with the admixture of many errors. Whereas man’s whole salvation, which is in God, depends upon the knowledge of this truth. Therefore, in order that the salvation of men might be brought about more fitly and more surely, it was necessary that they should be taught divine truths by divine revelation. It was therefore necessary that, besides philosophical science built up by reason there should be a sacred science learned through revelation… Although those things which are beyond man’s knowledge may not be sought for by man through his reason, nevertheless, once they are revealed by God they must be accepted by faith.” - Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (London: Burns Oates & Washbourne, n.d.).

This becomes the foundation of the Thomistic distinction between nature and grace. The realm of nature is that “lower” realm which deals with issues concerning the natural world, so math, science, politics and even certain aspects of theology can be satisfied within this lower realm. But the “higher” realm of grace is necessary for salvation, and so grace deals with issues of divine revelation, faith, Scripture, the church, etc.

Aquinas’ thinking in these matters would be carried over into the Renaissance, and they would remain in the background (so to speak) of the Reformation.

The key issue with Aquinas’ scheme here is not that he believes divine revelation is necessary for salvation. We whole-heartedly agree (although Reformed Christians differ strongly with Aquinas concerning how we are saved). The issue is that Thomas left the supposed realm of nature to the autonomous man. Students of apologetics will know this very well, for Thomas’ Five Ways are all built upon this idea that man’s natural reason can bring him up to the knowledge of God. By leaving the realm of nature free of the constraints of grace, he allowed for humanistic, sinful ways of thinking (for fallen man’s thinking is sinful, as seen above) in every realm of life, including politics and the state, but even in theology as well due to his natural theology.6

Now, how could Thomas get away with this? When you look around our world today, and you see the insanity of transgenderism and abortion, all manner of sexual licentiousness and blasphemy promoted in the media, secular science seeking to undercut a Biblical view of origins and a legion of other things, it might seem like the Christian should utterly repudiate any notion of leaving any aspect of knowledge to man’s natural reason. So why did Aquinas get away with this? Let me suggest to you that Aquinas got away with this because of what has been called sacralism.

Sacralism is a term that is mocked today by folks like Stephen Wolfe, but any serious student of church history will realize that it is very much a real concept. With that being said, I am using the term to refer to a broader reality than what it is typically reserved for, but I do not think it is unwarranted. Typically, sacralism refers to the intertwining of the church and state. This is a process that began with Constantine, but even he could not imagine what it would result in.

The middle ages see a constant power struggle between church and state, with the medieval western church ultimately winning. The event that pictures this well is when Pope Gregory VII excommunicated the Holy Roman Emperor, and made him beg in the snow for 3 days in Canossa, Italy. Therefore, in Aquinas’ day, the state was under the authority of the church. But when I talk about sacralism, I don’t just mean the intertwining of the civil and ecclesiastical powers, what I mean is that all of human life and knowledge payed its respect, in some way, shape or form, to the church. Every newborn infant was baptized, and this created a cultural dynamic wherein no aspect of human knowledge (within Christendom) was outside of the church’s jurisdiction.

When Aquinas is writing against Islam, he fully recognizes that they do not pay respect to Christ. But when thinking about those within western Europe, he had no concept of a thoroughly secular man. He had his division between nature and grace to be sure, but he could only do this because he never imagined that people would take the autonomy he granted them in nature and run with it.

However, this is exactly what happened in the Renaissance. Francis Schaeffer puts it very well:

"The simple fact is that this nature-grace division flowed over into the whole structure of Renaissance life, and the autonomous "lower story" always consumed the "upper."' - Francis A. Schaeffer, Escape From Reason, works vol. 1, pg. 223. Crossway Publishers

Schaeffer observes that permitting even a small amount of independent thought results in a complete shift towards autonomous humanistic reasoning. Schaeffer’s observations of this in art history are simply brilliant. In the humanism of the Renaissance, we begin to see shadows of the depraved nature of autonomous thinking, but before this could take place, the west needed one more revolution in its philosophy—the Protestant Reformation.

The Reformation and John Calvin

Let me say really quickly that I am not, even for a moment, granting the insane assertion so commonly made by Roman Catholics that the Reformers were rationalists, and because they abandoned the church’s authority that is why we have all the problems we have today. The Reformation was a divine gift from heaven above. The Holy Spirit worked amazingly to bring great light to the hearts and minds of Europe and a recovery of the true Biblical Gospel of justification by faith.

Key to all of this was a recovery (not innovation) of Biblical authority over and against the teaching of the western church. Martin Luther (1483–1546) observed (correctly) that church councils and popes had erred and contradicted one another, and declared, “my conscience is captive to the Word of God!” In the early writings of Luther we see an emotional breakthrough and escape from the shackles of dead, scholastic sophistry (which Aquinas represented in its most pure form). Luther championed Biblical authority as essential in his articulation of divine truth.

Luther deserves recognition as a man used of God in a mighty way at this time, but even he would not be consistent in his overthrowing of scholasticism in favor of Biblical authority. For example, his two kingdoms doctrine effectively reestablished a division between nature (secular) and grace (sacred) for Lutherans up to this day.7 This is where we need to remember that Luther was a man of his day. Now he was ahead of his time in many ways, to be sure, but my point is that he (like Aquinas) was living in a sacral society. This is seen in his views of church/state issues, of course, but I am referring here to this notion that there was no real conception (not even in the humanism of the Renaissance) of a life outside of the church. And so, Luther can, on the one hand, believe that the state has the right to punish theological heretics (such as he believed the anabaptist, Fritz Erba, to be) while also relegating the state to the realm of the secular.

Luther was a mighty man indeed, but is usually thought of more as a theologian of the heart rather than the mind. It is the second generation reformer, John Calvin (1509–1564), whose thought most concerns us now.

The most important place in Calvin’s writings concerning that old question of how do we know what we know? is, of course, Book 1 of the Institutes of the Christian Religion. But before we look at that, we get a glimpse into Calvin’s own views of the history of theology up to his lifetime in his letter in letter to the Roman Catholic Cardinal Sadeleto:

“Do you remember what kind of time it was when our Reformers appeared, and what kind of doctrine candidates for the ministry learned in the schools? You yourself know that it was mere sophistry, and sophistry so twisted, involved, tortuous, and puzzling, that scholastic theology might well be described as a species of secret magic. The denser the darkness in which any one shrouded a subject, the more he puzzled himself and others with preposterous riddles, the greater his fame for acumen and learning. And when those who had been formed in that forge wished to carry the fruit of their learning to the people, with what skill, I ask, did they edify the Church?” - John Calvin, Tracts and Letters vol. 1, pg. 40, Banner of Truth Trust

It is because of things like this that I really have a hard time comprehending those who act as if the Reformers whole-sale endorsed the fulness of scholastic thought. As I have said, they were influenced by the times in which they lived and this is definitely reflected in their views of church and state, but Calvin especially was willing to break free from the “twisted, involved, tortuous and puzzling scholastic theology”.

When writing in Book 1 of the Institutes concerning knowledge of God and of ourselves, Calvin does not relegate entire categories of knowledge into some autonomous realm, but rather he seems much closer to the Scriptural presentation we saw above. Calvin says,

“OUR wisdom, in so far as it ought to be deemed true and solid Wisdom, consists almost entirely of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. But as these are connected together by many ties, it is not easy to determine which of the two precedes and gives birth to the other.” - John Calvin, Institutes (Beveridge trs.) 1.1.1

Calvin sees an inseparable connection between knowledge of God and knowledge of the self. In contrast to Thomistic philosophy, which allows for fallen man an autonomous theory of knowledge before coming to know God, Calvin says,

“no man can survey himself without forthwith turning his thoughts towards the God in whom he lives and moves; because it is perfectly obvious, that the endowments which we possess cannot possibly be from ourselves; nay, that our very being is nothing else than subsistence in God alone… the knowledge of God and the knowledge of ourselves are bound together by a mutual tie, due arrangement requires that we treat of the former in the first place, and then descend to the latter.” - Calvin, ibid. 1.1.1-3

This does not mean that Calvin says you figure out God, and then yourselves. What he is saying is that the two categories of epistemology and ontology are inseparable.

Calvin, sounding very much like Romans 1, affirms the general revelation of God in nature that is apparent to all men, but that man in His rebellion suppresses this knowledge. Calvin therefore sees Scripture as necessary for a true knowledge of God. But unlike Aquinas, who sees man’s natural reason as sufficient in and of itself, but simply lacking the “upper story” knowledge of grace, Calvin says that the reason man needs divine wisdom is not simply because he is lacking more knowledge, but because his mind and judgements are skewed and directly opposed to God:

“For if we reflect how prone the human mind is to lapse into forgetfulness of God, how readily inclined to every kind of error, how bent every now and then on devising new and fictitious religions, it will be easy to understand how necessary it was to make such a depository of doctrine as would secure it from either perishing by the neglect, vanishing away amid the errors, or being corrupted by the presumptuous audacity of men. It being thus manifest that God, foreseeing the inefficiency of his image imprinted on the fair form of the universe, has given the assistance of his Word to all whom he has ever been pleased to instruct effectually, we, too, must pursue this straight path, if we aspire in earnest to a genuine contemplation of God;—we must go, I say, to the Word, where the character of God, drawn from his works is described accurately and to the life; these works being estimated, not by our depraved Judgment, but by the standard of eternal truth.” - Calvin, ibid. 1.6.3

Calvin is an incredibly bright light at this time in history. When he is being consistent with the Scriptures, he sees the wickedness of the human mind being “bent” towards sin and idolatry. He sees that true knowledge and wisdom is ultimately found in the knowledge of God.

Calvin’s thought will have an incredible impact upon the Reformed church down through the centuries. Cornelius Van Til will pick up on these key themes and develop them in his philosophy and apologetic. But Calvin would, like Luther, have his inconsistencies, especially in his beliefs concerning the state.

It would be, in my opinion, a proper application of Calvin’s thought that, if true knowledge and wisdom were to be found in the knowledge of God, and if fallen man’s intellect is skewed towards idolatry, that I would not look to fallen man’s reason for my civil ethic but that, rather, I would look to what God actually said in His word concerning civil ethics. But Calvin, a man of his day at this point, adopted the thinking of those before him that issues concerning a state were a realm in which man’s natural reason sufficed, and thus he says:

“For there are some who deny that any commonwealth is rightly framed which neglects the law of Moses, and is ruled by the common law of nations. How perilous and seditious these views are, let others see: for me it is enough to demonstrate that they are stupid and false… The allegation, that insult is offered to the law of God enacted by Moses, where it is abrogated, and other new laws are preferred to it, is most absurd. Others are not preferred when they are more approved, not absolutely, but from regard to time and place, and the condition of the people, or when those things are abrogated which were never enacted for us. The Lord did not deliver it by the hand of Moses to be promulgated in all countries, and to be everywhere enforced; but having taken the Jewish nation under his special care, patronage, and guardianship, he was pleased to be specially its legislator, and as became a wise legislator, he had special regard to it in enacting laws.” - Calvin, ibid., 4.20.14-16

Now it should be noted that what Calvin likely has in view here are the many radical anabaptists who were essentially denying the validity of civil government. This undoubtedly influenced his harsh condemnation at this point. Calvin is not here interacting with the responsible, thoughtful reformed theonomists of the last century such as R.J. Rushdoony or Greg Bahnsen. But as Rushdoony points out, Calvin isn’t consistent here, for Calvin also believed that the law of Moses did have a civil use in curbing sinners (see Institutes 2.7.20):

“But Calvin did not apply these ideas. Instead, he surpassed Luther and insisted that the state must enforce both tables of the law, that the state, in short, must be Christian, not "natural" or "neutral," a possibility he denied. Civil government, he held, must enforce God's law. For Calvin, "the rule of life" which God has given us is "His law."” - R.J. Rushdoony, The One and the Many, pg. 277, Ross House Books

And so we see with the Reformation a magnificent renewal in human thinking grounded in God and His revelation. What this is all going to lead to, then, is a split between theology and human philosophy, which persists with us to our very day.

You might be puzzled by this notion. How could a strong return to Biblical authority in our thinking have any impact on human philosophy becoming more thoroughly secular? Well, once theology became more and more centered upon divine revelation, autonomous reason began to be pushed out, but it needed somewhere to go. And thus John Frame sees the post-reformation period as the beginning of the rebirth of secular philosophy:

“The Reformation marked a rebirth of biblical Christian thought, emphasizing as had not been done in many centuries the biblical metaphysic (absolute-personality theism, creation), biblical epistemology (based on revelation and the working of the Spirit), and biblical ethics (God's law applied to God's creation by redeemed subjects)… But in the seventeenth century there was a similar rebirth in non-Christian thought, in which secular thinkers renewed and pressed the claim of autonomous knowledge more consistently than anyone since the Greeks. Indeed, this rebirth echoes strikingly the beginning of philosophy itself in Greek Asia Minor… The philosophers sought for the first time to understand the world by reason alone. The same may be said of the seventeenth-century revival of secular philosophy. Although these philosophers were unavoidably influenced by past philosophical and religious movements, they resolved not to regard any of these as authoritative. They saw human reason as autonomous, as self-authenticating, and as the chief arbiter of all philosophical controversies.” - John Frame, A History of Western Philosophy and Theology, pg. 177, Presbyterian & Reformed

To make this easier to understand, remember back to Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas was a philosopher and a theologian. This is typical of the medieval period. There were not philosophers over here, and theologians over there. But in the post-reformation period, there will be a firm split. It is not that philosophers no longer said anything about God; it was that they began their philosophy on purely autonomous grounds, whereas Aquinas at the very least said that divine revelation should correct natural reason.

René Descartes and the Rise of Secular Philosophy

With the post-reformation split between Biblical theology and human philosophy, René Descartes (1596-1650) represents the first “modern philosopher”. To put this in a chronological perspective, he is born only about 40 years after Calvin’s death. He is contemporaneous with theologians such as Gisbert Voetius (1589-1676), Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) and John Owen (1616-1683). Though he was accused of atheism by Voetius, he died a French Roman Catholic, and had even hoped that the Catholic church would adopt his philosophy over and against that of Aquinas!

Now why would Voetius accuse Descartes of atheism? It is because Descartes’ philosophy, being grounded in purely autonomous reason, led him to skepticism and doubt. Ironically, in a journey to discover truth that he was absolutely certain of, he quickly discovered that he had no real reason to be certain of anything! Sense experiences could not make him certain of truths such as “I am sitting by the fire” or “I have two hands” because it was always possible that his senses were unreliable, or that it was all part of some vivid dream. Even in the area of mathematics, how could he be sure that he was not being deceived by some evil demon to think falsely?

Eventually, Descartes realized that the only thing he could really be certain of was that he himself was doubting, and if he was doubting, then that means that he at least had to exist in order to do the doubting. And hence, his most famous statement is “cogito, ergo sum” or “I think, therefore I am”. He thinks, because he doubts, therefore he must exist otherwise he couldn’t think. And so he proved his own self-consciousness and the existence of himself, but he thought that this could prove the existence of God as well. For you see, he not only knew he existed, and knew that he knew this, but he also knew that in his mind there was a concept, or an idea of God. He thought that there must be some explanation for this idea, and so the idea must have been planted in his head by God, but in order for God to do that, He would have to exist! And in a similar fashion to Anselm’s ontological argument, he believed that because existence was a part of his concept of God, that there must really be an existing God in order for this concept to make any sense. But let’s be very clear about something: divine revelation played no part in his argumentation here. He tries to argue for God based upon reason alone, using his own mind as the starting point.

And while you may find it interesting to think through Descartes’ philosophy, there is a fundamental flaw that brings his whole system crashing to the ground. Based upon his own reason alone, Descartes proved nothing more than his own self-consciousness. If that is the only thing he is certain of, how can any of the thoughts in his mind have anything to do with stuff outside of his own mind, including his own body? How do you close the gap between the thoughts in your head and the real existing world?

Descartes’ solution to this is really nothing more than pathetic. He posited that mental substances (thoughts in the head) and material substances (things existing in the material world, or extended in space) interacted just enough inside the body’s pineal gland. Now the pineal gland, so the scientists tell us, is the gland in your brain that produces melatonin, which helps you sleep. But in the 17th century, no one really knew what it did. And so Descartes’ pathetic solution to this problem he created has become a joke among philosophers, Christian and non-Christian alike.

Now I decided to briefly go over Descartes here not just because of where he stands chronologically, but because his system of thought is a great case study in what happens when you divorce God’s revelation from your thinking—you devolve into arbitrariness and skepticism.

Now history is going to keep going. Philosophy will evolve, just as Christian theology is going to continue to be shaped. The Westminster Confession of Faith is written in Descartes’ lifetime, which represents (although I am personally a Baptist and adhere to the London Confession of 1689) a great example of theology grounded in the revelation of God. But human philosophy is going to continue to drift further and further away.

Though Descartes himself was a theist, he really had no reason to be if one grants his skepticism. This is why Voetius thought Descartes was so dangerous, and he sensed that atheism was on the rise in the Dutch society. After Descartes, we will see the rise of British Empiricism with such men as John Locke (1632–1704) and David Hume (1711-1776). These men are by no means unimportant, but the next thinker we will be going over will not just adopt rational autonomy as his method (as did Descartes and these other men), but he will seek to defend this way of thinking, and in doing so has become perhaps the most consequential philosopher in the modern world.

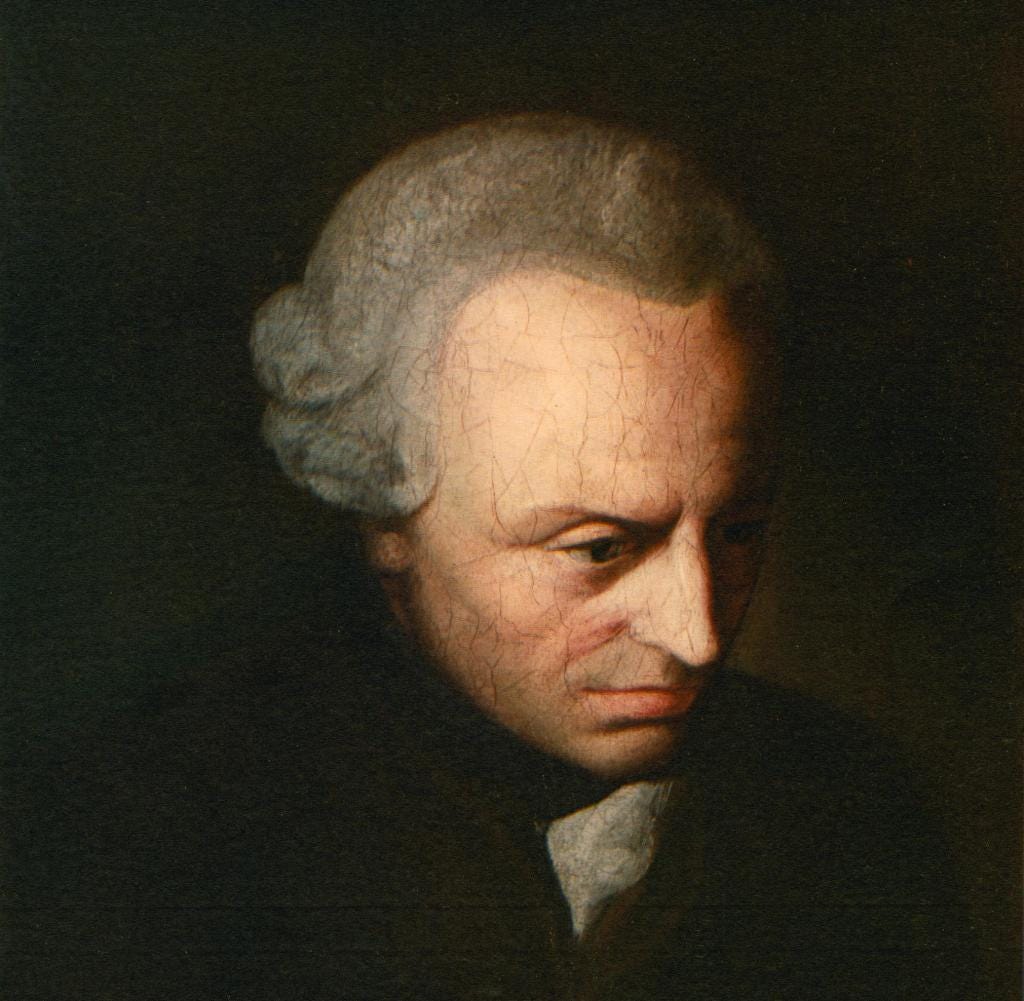

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) has been considered a “Copernican revolution” in human philosophy. Kant was a rationalist (as was Descartes), which means that he believed he could come to true conclusions by way of reasoning from certain axioms, or starting points. But it was in reading the empiricist (empiricism says truth is to be found through observation of evidence) David Hume when he was awakened from his “dogmatic slumbers”, for Hume challenged Kant to not simply assume his rational way of thinking, but to give an explanation for reason itself. So instead of just asserting an axiom as a starting point, tell us why it is there at all, and tell us what it is you are doing as you are reasoning. And so Kant’s most famous work is a Critique of Pure Reason, for he is giving an examination into reason itself.

The key thing Kant does is divide reality into two worlds, so to speak. The noumenal world (the world of things as they are apart from our experience) and the phenomenal world (the world of our own experience, how things appear to us). Kant asserts that knowledge is possible, and so he is going to try to explain to us what the preconditions for the possibility of knowledge are. In doing so, he is going to try to provide us with that bridge between the phenomenal and the noumenal.

Put simply, Kant believed that this gap was bridged when the human mind itself (the phenomenal) gave structure to and made sense out of its experience (the noumenal). Unlike Locke, who believed the mind was a tabula rasa (blank slate), Kant does not believe that the human mind is merely passively receiving data. But the mind, for Kant, is imposing a structure upon the data itself. The mind is like the ice cube tray which shapes the water of our experience.

What happens, according to Kant, is that upon encountering the raw data, the mind begins to give shape and order to the object so that it can be perceived. Once perception is accomplished, then the mind categorizes the object with such things as quantity, quality, purpose, etc. All of this is held together by a “unity of conscience”. Unlike Descartes, who thought self-consciousness was a thing to be proven, Kant presupposes consciousness as that which binds together the phenomenal and the noumenal, and thus allowing the mind to interact with and know the world around it.

If you find Kant confusing, you are not the first. I have tried my best to simplify his thought, but the most important thing to remember, even if you forget everything else I’ve said, is that for Kant the activity of the experiencer is what ultimately gives grounds to knowledge. Everything, whether God or the desk I am sitting at, is ordered and understood by my autonomous mind. And once you have created a situation like this, there is no more room for God to speak to you and challenge your line of thinking.

And so, even though Kant believed he was saving science and making room for faith, he was ultimately destructive to faith (and science, for that matter) by placing knowledge and understanding not in the revelation of God but in the autonomous mind of man.

Now, why on earth spend anytime talking about this secular philosophy? It is confusing, strange and even laughable at times. Well, you see, we as Christians have to live in this world. And we need to interact with and speak to this world, not only in terms of our apologetic, but even in our ethics as well. And so, when we see the nonbelieving world cut itself off completely from divine revelation, and thoroughly secularize itself (as it has done in our own day) Christian thinkers need to seriously consider how to interact with the world.

I mentioned that the reason why Thomas Aquinas could get away with handing the realm of nature over to the autonomous man was because of the sacral society in which he lived. But after men like Descartes and Kant have hit the scene (along with countless other factors, of course) we no longer live in that same context as Aquinas. And thus the dangers of granting any aspect of knowledge to autonomous man, which may not have seemed as obvious in Thomas’ day, or in the days of the reformers, once society has moved beyond that point the dangers are more apparent. You cannot hand civil ethics, for example, over to natural reason when the average person believes it is morally acceptable for men to have sex with men, or to murder unborn children in the womb, or any of the other perverse things we see in our society.

Stephen Wolfe, in his The Case for Christian Nationalism at one point makes an observation that I think is very good, but I think the application he makes is bad. He says that critics of his position will look at history to point out the dangers that have developed when society looked like what he argues for in his book. What Wolfe says is that we should also learn from history to see what happens when civil society is left “neutral”. Wolfe is right to say we should learn from all of our history, but if this is the case, then why simply revert back to the old ways of natural law and princes? Why not observe that there are flaws in both, and begin looking in a more Biblical direction?

I believe that Cornelius Van Til (1895-1987) has done this in the realm of apologetics. With the Bible as his ultimate authority, and building off of Calvin, Warfield and Kuyper; Van Til developed a consistently reformed and Biblical way of doing apologetics. He recognized that all human knowledge has its origin in the Triune God, and that it was false to seed any ground to the autonomous mind of the rebellious sinner, and so what he did was demonstrate the existence of God by way of transcendental argumentation—think, the impossibility of the contrary. His student Greg Bahnsen (1948-1995) took this apologetic approach and applied it practically, such as in his famous debate with the atheist Gordon Stein. But Bahnsen saw that, in the working out of a consistently Biblical worldview, if all knowledge comes from God, then our knowledge of ethics must also come from God. And so he became one of the leading voices promoting Theonomy (God’s Law) as the standard in Christian ethics. If God spoke to a man named Moses on Mt Sinai, then we do not need to appeal to the hostile fallen reason of autonomous man. We must simply listen to what it is that God has said.

After our brief historical overview of theology and philosophy, one can see why the ideas of Van Til and his students became more and more necessary after the time of the reformation. Although the “novelty” of the Van Tillian approach is often used as an argument against its validity (not that it is a necessarily good argument), there is a perfectly valid historical reason why these ideas were more clearly defined when they were. The simple truth is that Van Til, and Bahnsen for that matter, was faced with a different world than the reformers. It is not that I think there is a major radical discontinuity between Calvin and Van Til (Van Til certainly didn’t think there was) we must remember that the two men were answering different questions.

Just like we do in our own spiritual lives, the church is sanctified as it ages. It is not that the Bible changes. What the Bible says about the existence of one God, and three Persons identified as this one God, was always true, but no one would deny that the church had a clearer understanding of this post Nicaea. The church’s understanding of doctrine has always been shaped by conflict (just think about how clearly you understand justification by faith because Paul defended this against the Judaizers, as did Luther against the papists) and I believe that the Van Til school of thought has a clear, Biblical understanding of apologetics and ethics because of the battles that have taken place in the thinking of the unbelieving world.

It seems odd to me that when the world has moved on far past how things were in the days of medieval Europe, that modern Thomists still want to engage in apologetics and ethics as though nothing changed. But things have changed, and they have shown us that it is a deadly error to give over any aspect of knowledge to rebel sinners.

Now I know full well that the way of thinking I am advocating for is mocked as foolish, Biblicist, fundamentalist or whatever. But have we forgotten that Paul declared that what was foolishness to the world is the power of God? (1 Corinthians 1:18). I suppose it is foolish in the sight of this world to point to Leviticus 18 and say “man shall not lie with man as with a woman”, but then again, they are the ones actually doing this and what is more foolish?

My work as an abolitionist has shown me the errors in natural law way of thinking (read more about this here). We must be Christians who are not ashamed to be called Biblicists, but we must recognize that “all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” are hidden up in Christ Jesus our Lord (Colossians 2:3).

Semper Reformanda

Quoted from his lecture on natural law at Reformcon 2025, not available online at the moment.

I am not using this term here to refer to ethical matters, as is explained.

Called in theology, the noetic effects of sin.

I think that Maimonides had a far more prominent influence on Thomas than perhaps many modern Thomists would care to admit, but I digress.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (London: Burns Oates & Washbourne, n.d.).

Although Aquinas will need to eventually fall back on faith to get the man to believe, ironically making the Thomistic apologetic closer to fideisim than presuppositional apologetics, as Dr. Greg Bahnsen pointed out in numerous places.

I do not believe this was his intention, Aquinas strikes me as sincere in his piety.