Tolkien Should Have Read Van Til

Tolkien, allegory and worldview

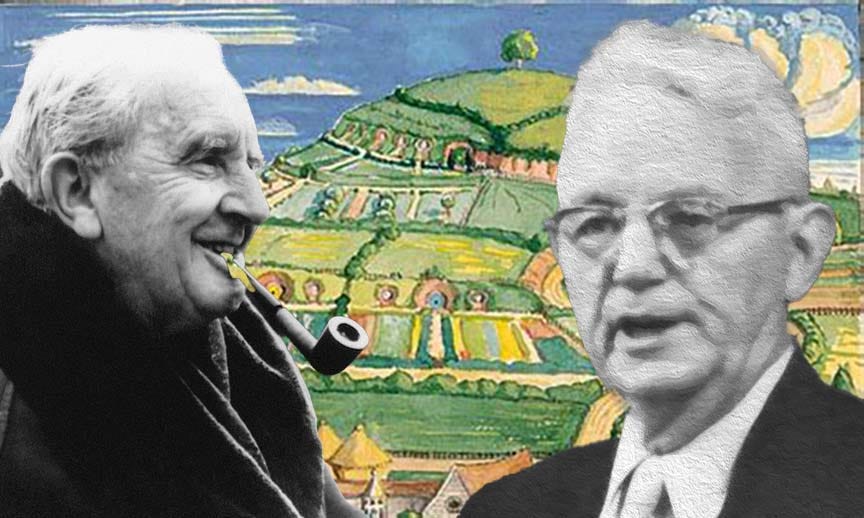

Sometimes I derive pleasure from taking the random thoughts that flow to the top of my head and saying them out loud. One such instance occurred a little while ago when I tweeted (or posted, whatever) “Tolkien should have read Van Til”. Now, admittedly, this was intended to be somewhat of a joke, but there is more to it. J.R.R. Tolkien is probably the most well-known Roman Catholic writer (perhaps even just writer) of the 20th century (although he is most well known for his fiction) and Cornelius Van Til is, at least one of, the most well-known Reformed Protestant writers of the same century. Tolkien was born just about 3 years before Van Til, and so while I might be the first person to ever put these authors side by side, it is interesting to think of them as contemporaries. I recently listened through The Modernity Lectures from Dr. George Grant and was absolutely fascinated when he included Van Til (along with Tolkien) as one of the great post-WWI writers.

Now, I think because I have read so much from Van Til; I appreciate these little details more than most. Van Til taught me to see human knowledge as connected, so to speak. In his writings, he pushes us beyond fact to a philosophy of fact, that all human knowledge is connected and united (without losing its individuality and particularity) due to the reality that every fact is interpreted according to one’s larger world-and-life view. “Facts and interpretation of facts cannot be separated. It is impossible even to discuss any particular fact except in relation to some principle of interpretation.”1 And so, an honest assessment of our knowledge and understanding of the world around us will reveal that we are biased, shaped and influenced by the times and places in which we live. We can not isolate, or atomize (to use a philosophical term) any individual piece of our knowledge.

And so, our experience, whether it be world wars or our religion, is going to pour into how we evaluate and understand everything. Van Til’s purpose in stating this was in defense of the Christian faith. When confronting the unbeliever, we cannot simply argue over facts. We must push beyond to discuss the interpretation of facts. Brute facts are mute facts, as he once put it. The Christian sees every individual fact as part of God’s overarching plan in history.

Now, what does this have to do with Tolkien? Well, ever since Tolkien initially published works like The Hobbit and especially The Lord of the Rings, there has been discussion concerning the meaning of his stories. Is The Lord of the Rings an allegory about the world wars? Tolkien’s Catholic faith? Many people are quick to defer to Tolkien’s own words, when he explicitly stated in the foreword to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings “As for any inner meaning or ‘message’, it has in the intention of the author none. It is neither allegorical nor topical.”

And so, clearly the story is not an allegory, right? This might seem to be the case, especially when he goes on to say, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence.” Consistent with this is what Tolkien once wrote in a letter to young medical student, Herbert Schiro, “There is no 'symbolism' or conscious allegory in my story. Allegory of the sort 'five wizards = five senses' is wholly foreign to my way of thinking. There were five and that's just a unique fact of history. To ask if the Orcs 'are' Communists is to me as sensible as asking if Communists are Orcs.”

But then, here is the thing. You go and you read The Lord of the Rings and you begin to see parallels between the events/characters described in the story and things in the real world. It’s quite hard to read of Gandalf’s return in white without thinking about the resurrection of Jesus Christ. It is equally difficult to read about Saruman’s dominion in the Shire without thinking about distributist economics, which were so prevalent in the regimes of the 20th century. If Tolkien says these things are not allegorical, why do his readers so readily see these connections?

I haven’t been quite fair in my presentation of those quotes from Tolkien, which was to serve for dramatic effect. Tolkien fans probably know that these quotes actually continue. In his foreword to the second edition of LotR, after delivering his scathing rebuke of allegory, he says, “I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of the readers. I think that many confuse ‘applicability’ with ‘allegory’; but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.” Also, in the letter referenced earlier, he says,

“That there is no 'allegory' does not, of course, say there is no applicability. There always is. And since I have not made the struggle wholly unequivocal: sloth & stupidity among hobbits, pride and escapism among Elves, grudge and greed in Dwarf-hearts, and folly and wickedness among the 'Kings of Men,' and treachery and power-lust even among the 'Wizards,' there is I suppose applicability in my story to present times. But I should say, if asked, that it is not really about Power and Domination: that only gets the wheels going; it is about Death and the desire for deathlessness. Which is hardly more than to say it is a tale written by a Man!”

You see, the basic idea for Tolkien is that his story is not intended to be a 1:1 allegory in the way that C. S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, or John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress is. When you read Bunyan, for example, his story has a pretty narrowly defined meaning. His protagonist has the explicit name Christian, after all. Bunyan is making pretty explicit points throughout the story, in such a way that it is quite possible for the reader (however unlikely) to get it wrong. Most versions of the book you find today actually contain explanatory notes among the Scripture references. The author consciously decided what the story means before you have read it.

What Tolkien wants to say is that when he sat down to write The LotR he was not sitting there thinking, “The Shire represents England, the One Ring the atom bomb, or Gandalf Jesus Christ”. The story is meant to be an invented world that can stand on its own two feet. But we have to ask the question, was he right?

I realize how stupid that sounds. Obviously, Tolkien is right! He wrote the thing after all! But in my view, it’s not so simple as that. If you really think about it, this is a question of epistemology and worldview. You see, it might be possible that a non-allegorical story is, in a certain sense, impossible.

As brilliant as Tolkien was, he even acknowledges in the above citation that his ideas did not spring up out of nowhere. There is also a fascinating quote from him in another letter in which he states, “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.”2

That line “unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision” is quite amazing, because it indicates some development in Tolkien’s thinking on the matter. He realized after the fact just how much his Roman Catholic faith influenced his story. And for someone who explicitly denied allegory in his work, he nevertheless talks about religious “symbolism”. Perhaps against his own intentions, his worldview influenced the story he told. He was not able to break out of his own mind.

The Point of This Whole Thing

While fantasy literature might not seem nearly as important as what I normally discuss on here, I just thought that Tolkien’s heavily debated relationship with allegory served as an interesting case-study in epistemology and worldview. And so, yes, I think that if Tolkien had taken the time to interact with the Dutch-American Reformed Philosopher and Apologist Cornelius Van Til (as unlikely as this would have been) he would’ve had these things more sorted out in his own mind. This doesn’t mean he would’ve changed his stance on allegory, but he would’ve had a clearer understanding of how his own beliefs directly impacted what he wrote. You cannot separate the art from the artist, nor the artist from his worldview.

On a much more serious matter, Tolkien should have read Van Til because, unlike Tolkien’s strict pre-Vatican II Roman Catholic faith, Van Til’s Reformed theology possesses the true Gospel. Some of the most devastating critiques of the Roman Catholic worldview are to be found in the dutchman’s works. As brilliant a man as J.R.R. Tolkien was, appeals to Marian intercession and a trust in the Mass as a propitiatory re-presentation of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ cannot make him righteous in the sight of a Holy God. Only the true, saving, Biblical Gospel of justification by faith alone in Christ alone, and a holding on to His imputed righteousness will account for anything on the day of judgement.

With that being said, can a Reformed/Protestant Christian read Tolkien? Even love Tolkien? I think so, and I actually do so. There is profit to be found in the artistic expressions of both believers and nonbelievers, and those of a false religious system. All the truth and beauty expressed in Tolkien’s writings might be said to be both true and beautiful despite his Roman Catholicism. And those of us with the true Gospel can appreciate and be blessed by these things.

With that said, although I don’t really know what to do about this, a personal desire of mine is for presuppositionalist types to get into the arts. People have taken Van Til’s ideas and applied them beyond the realm of apologetics, to education, politics, economics and a host of other fields. And maybe I am just unaware, but I have yet to see the followers of Van Til break into the arts. Oh well, maybe one of my readers will become a great Van-Tillian poet or something.

Oh, by the way, this article is a good analysis of Tolkien’s relationship with allegory and helped me find various references to the discussion in his letters: Majesty and simplicity: on Tolkien and allegory

Cited in Van Til’s Apologetic, Readings and Analysis, Dr. Greg L. Bahnsen, P&R, 1998 page 38