In Defense of Protestant Piety

Living in this world as citizens of another

It struck me this past week as I was reading of the “pillar-saints” of yesteryear, the lengths to which some Christians have gone to demonstrate their (seemingly sincere) devotion and piety.

If you don’t know who the pillar-saints were, they were a handful of ascetics in the 5th century, most notably St. Symeon the Stylite (390-459), who became so dissatisfied with the things of this earth, that even the normal habits of the ascetics in the cloisters of fasting, prayer (and of course, the shunning of women) were not enough for him. Symeon first joined the monastic life when he was a boy of just 13 years old, upon hearing the Beatitudes and being impressed with its other-worldly vision of purity and humanity. He went to live in one of the cloisters where he would embark on lengthy fasts where he lay several days at a time without food or drink (except Sundays), believing that this denial of self was spiritual enlightenment. During the lenten season, he would go the whole 40 days without any food or drink at all. Eventually, his quest for heaven saw him take to life as a hermit, upon a mountain wearing an iron chain on his feet. Still unable to reach God by this effort, he traveled about 40 miles east of Antioch (a two day’s journey) where he erected a great pillar to live atop of. No shelter from the wind, rain or sun and only living off of the provisions of his followers. He made a series of these pillars, each taller than the last, and lived this way for 36 years. When he died, the pillar he lived upon measured about 50 ft in height.

Admittedly, these “pillar-saints” represent the most extreme of the ascetics. But the basic practice of monasticism neither began nor ended with them. The monastery would remain a part of the Christian church until the Protestant Reformation, and forms of it still exist in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox branches of “Christendom”. The church, its doctrine, and the world as a whole have been deeply impacted by the monastic lifestyle. Martin Luther himself began his spiritual journey as a monk.

Protestants have, for the most part, regarded asceticism and monasticism as a departure from the actual lifestyles and teaching of the Apostles. In the book of Acts, we don’t see the Apostles retreating from the world to live in the desert, in caves, monasteries and certainly no Apostle of Jesus Christ ever dreamed that it was a Christian virtue to live atop of a pillar for decades on end. We see the Apostles taking Christ’s message and going into the streets, into the major cities and debating in the Synagogues with the Jews, and refuting the vain wisdom of the Philosophers at the Areopagus. Their enemies said of them that they had “turned the world upside down” (Acts 17:6).

What we see in both Old and New Testaments is that God is very much concerned with the things of this earth. Jesus came to this world proclaiming the good news of the kingdom, the messianic expectation of world transformation and renewal. But as the Old Testament became allegorized out of its original meaning, and the church began to be influenced by Greek philosophical ways of thinking, neo-platonism in particular, we see the church beginning to retreat from the world, and from the culture, in those early centuries. Chiliasm (primitive forms of premillennialism, believing that the millennium was soon at hand) and monasticism were the tangible results of this. The church began to believe that spirituality consisted exclusively in things above, with the things of this world being viewed as either less important or, at times, even opposed to the things of God. While the early church saw societal reformation in the opposition of the Christians to infanticide and the gladiatorial games, monasticism saw the church moving away from these tendencies, and many historians will trace the rise of monasticism as coinciding with the decline of the Roman Empire.

Essentially, in monasticism, we see the church abandoning God’s mission and plan to save culture, to save society as well as our souls.

But at this point, someone will say that the Scriptures do teach that we are pilgrims on this earth, sojourners and exiles (Hebrews 11:13, 1 Peter 2:11) and that our citizenship is in heaven (Philippians 3:20). Jesus tells us, quite explicitly, that we are, in fact, to deny ourselves (Matthew 16:24, Mark 8:34, Luke 9:23). As I have pointed out, the errors of millenarianism, and ascetic retreatism someone else might, just as fairly, point out the dangers of the social Gospel of the early 20th century, many of its proponents holding to a form of postmillennialism.

Any fair-minded Christian being the least bit charitable will have to confess that there have been extremes in errors of both directions. The monastics, creating a radical dualistic separation between the earthly and the heavenly, and also those liberal Christians who have essentially conflated the two, seeing the work of the Gospel almost exclusively in state programs to bring about earthly change.

It is not my intention in this post to discuss the distinct roles of the church and state, spheres of sovereignty, cultural engagement or eschatology. My writings on those topics can be found by going to the Ethics and Culture page on my Substack. What I want to do here is write for my fellow Christians, particularly fellow postmillennials, who see the errors of the retreatist and almost neo-platonic fruit of dispensationalists and even R2K pietists and offer a defense of what I think is balanced Protestant Piety.

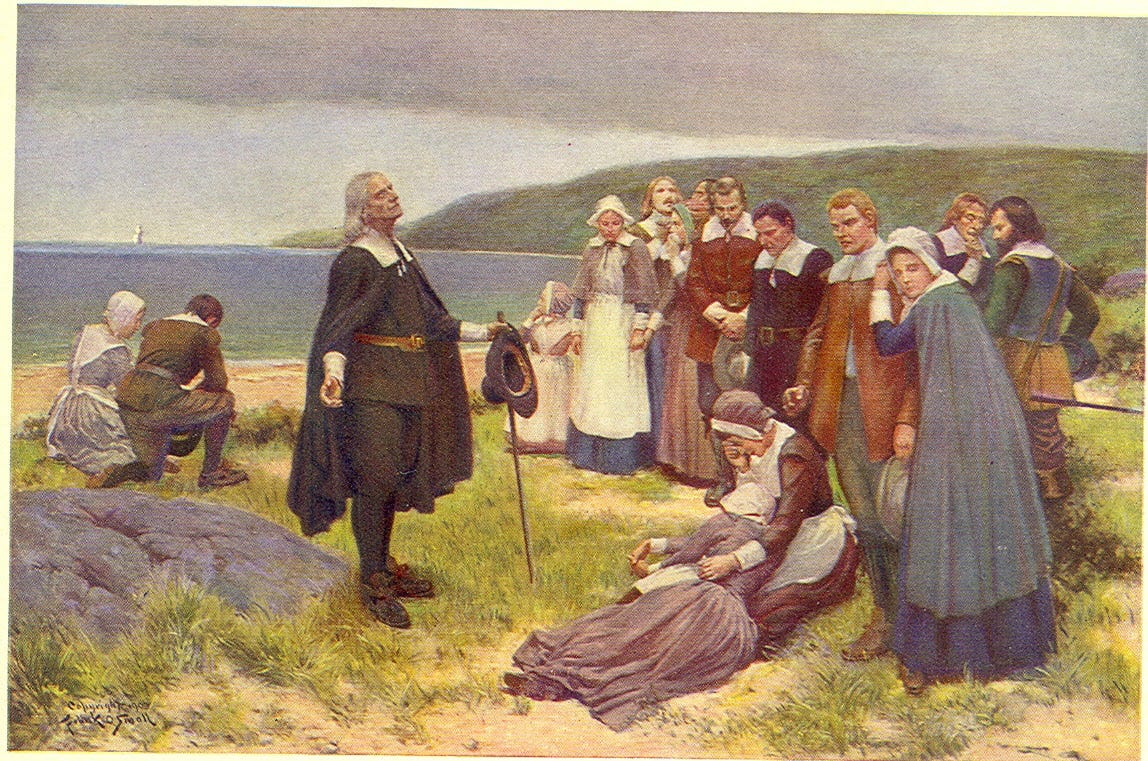

An examination of history, as I have said above, will demonstrate for us that the Christian church has struggled immensely, with striking the right balance between living on this earth and living as citizens of another world. But if we had to pick one group of Christians who, at least for a time, seemed to get it right, we might choose the Puritans.

The Puritans, when they’re really being pure, seem to capture for us the right balance between a deep, spiritual piety, and an attitude that is concerned with the well-being of the nation and culture around them. They do this, not, by creating a radical distinction between the kingdom of earth and the kingdom of heaven, but instead what they do is approach all of life, from the prayer-closet to the state-house, with a total Christian philosophy, or dare I say, worldview. The Puritans exemplify for us, at times, almost a Biblicism in trying to direct and govern all of life according to the Scriptures. The great Reformed Anglican, J.I. Packer, has written:

“Puritanism was essentially a movement for church reform, pastoral renewal and evangelism, and spiritual revival; and in addition—indeed, as a direct exposition of its zeal for God’s honor—it was a worldview, a total Christian philosophy, in intellectual terms a Protestantized and updated medievalism, and in terms of spirituality a reformed monasticism outside the cloister and away from monkish vows.

The Puritan goal was to complete what England’s Reformation began: to finish reshaping Anglican worship, to introduce effective church discipline into Anglican parishes, to establish righteousness in the political, domestic, and socioeconomic fields, and to convert all Englishmen to a vigorous evangelical faith. Through the preaching and teaching of the gospel and the sanctifying of all arts, sciences, and skills, England was to become a land of saints, a model and paragon of corporate godliness, and as such a means of blessing to the world.” - J.I. Packer, A Quest for Godliness, pgs. 38-39, Crossway Publishers

For the Puritans, there was not a choice between devotional piety and cultural engagement. Since they were rip-roaring Calvinists, God was sovereign over everything, and therefore His Word had bearing and implications upon all aspects of life. They worshipped, read Scripture and prayed as Christians, and they also went to work, school, or even politics as Christians.

Not being without its faults, there is really something to be admired about those Puritans in New England who looked out towards the wilderness in America and saw there the opportunity to construct a thoroughly Biblical society. A form of theonomy can even be found in John Cotton’s, An Abstract of the Laws of New England (1641).

Nevertheless, in all this, the Puritans still lived with what has been called a “pilgrim mentality”. The Christian life was still lived with an eye for eternity, as it were. So you could have John Owen, as an example, personally accompany Oliver Cromwell during the English Civil War, being named an official preacher to the state, advising and counseling Parliament to show mercy to the Irish, and being the same man who writes lengthy treatises on mortifying sin, and living in communion with the Triune God. Richard Baxter, though less orthodox than Owen, similarly supports and occasionally accompanies parliament (in the early days of the war) involving himself in temporal, military affairs, and then goes on to write an over 800 page book on heaven.

The point I am trying to make is that despite their concern with this-side-of-heaven earthly affairs, the Puritans never lost their spiritual devotion. Anyone who takes and reads something like Thomas Watson’s “A Godly Man’s Picture”, or Jeremiah Burroughs’ famous work, “The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment” knows that these were men who were sincerely pastoral and devotional, exhorting Christians to prayer, the reading of Scripture and practical godliness. Richard Sibbes’ “The Bruised Reed” is one of the best medications for the hurting soul in existence.

With this brief commentary on the Puritan outlook, might I encourage you, dear Christian, not to stop your engagement and concern with very real and very important matters that pertain to this life, but also not to forsake spiritual discipline along the way. Count all things as rubbish in comparison to the “surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus” that by “any means possible” you may “attain the resurrection of the dead” (Philippians 3:8-11). Oh brothers, I plead with you to give yourselves to prayer and the reading of Scripture. Seek to cultivate real and genuine godliness in your hearts and bodies.

The Apostle Paul was not an ascetic, but he taught that we ought to examine ourselves “to see whether you are in the faith” (2 Corinthians 13:5). Evaluate your life, evaluate your sanctification. Are you growing in holiness? In the “grace and knowledge of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ”? (2 Peter 3:18). In 1 Corinthians 9, the Apostle Paul compares the spiritual life of the Christian to a runner in a race. There is a goal at the end, something that you are looking for, that you must stay dedicated in order to reach. And so Paul says, “I discipline my body and keep it under control” (1 Corinthians 9:27). In this way, Paul lived on this earth. He did great and wonderful works, he debated philosophers and Jews in the public square, he stood before kings and rulers, he turned the world upside down. And, in all of this, he lived as one whose “citizenship is in heaven” awaiting “a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ” (Philippians 3:20). For we need to be good, holy and spiritual Christians ourselves if we are going to change the world!

Paul lived like the saints described in Hebrews:

“These all died in faith, not having received the things promised, but having seen them and greeted them from afar, and having acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth. For people who speak thus make it clear that they are seeking a homeland. If they had been thinking of that land from which they had gone out, they would have had opportunity to return. But as it is, they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared for them a city.” - Hebrews 11:13–16 (ESV)

We have seen the ascetic and pietistic abuses of all these things, and it is right—nay, it is necessary for us to resist those errors. But we are hurting ourselves, spiritually, if in our resistance of error we forsake what is right about these basics of spiritual discipline.

Before we end here, if I could give my readers just one practical piece of advice, it would be not to fall in love with the things of this world. The Apostle John tells us as much:

“Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world—the desires of the flesh and the desires of the eyes and pride of life—is not from the Father but is from the world. And the world is passing away along with its desires, but whoever does the will of God abides forever.” - 1 John 2:15–17 (ESV)

This is not navel-gazing, neo-platonic pietism that renders a man so heavenly-minded he is no earthly good. This is the Apostle John speaking, in inspired Scripture. It doesn’t mean we throw up our hands, saying, “this world is not my home” and neglect the concerns and affairs of culture and society. But it does mean that we have to engage those things with the Pilgrim mindset that our ultimate delight and satisfaction is not in the transformation of the temporal world but is rather in the Person of Christ Jesus and fellowship with Him. Do not find your greatest joy in your possessions, in your relationships with others, or even in your work. Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, as it were (Matthew 6:19). In all things, be content with what you have. This is one of the key virtues to be learned in this life. Recognize those things as gifts from the Father above (James 1:17) and really, truly enjoy them. God wants you to enjoy the temporal gifts He gives! But do not forsake the Giver for the gifts, but taste Christ in the sweet wine He gives you to drink. All of life is to be lived for Him, then, in this way.

From the prayer-closet to the state-house, “Christ is all, and in all” (Colossians 3:11)